"White Rock": Not White, Not Rock

White Rock got its nickname more than 30 years ago, when scientists first spotted the feature on the floor of Pollack Crater in images taken by the Mariner 9 spacecraft.

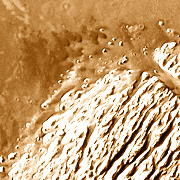

Pollack, which is about 90 kilometers (55 miles) wide, has a dark floor, especially over its southern half, where White Rock lies. At the time of Mariner 9, rather contrasty image processing gave White Rock, which measures about 15 by 18 km (9 by 11 miles), a chalky-bright appearance.

The brightness led many scientists to propose White Rock was made of water-deposited sediments, like the salty residue of a dried-up desert lake. (In 2004, just such deposits were found in Meridiani Planum by NASA's Opportunity rover.)

In 2001, however, scientists working with the Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES) instrument on NASA's Mars Global Surveyor orbiter found that White Rock has a dry origin and is built of wind-blown sediments. The bright blocks and ridges have the same brightness as light-colored, dusty regions elsewhere on Mars, and White Rock's spectra likewise match these and show no trace of water.

The image seen here was taken at visible-light wavelengths by another instrument, the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS), on a different spacecraft, NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter.

Soft Hills

The wind-sculpted ridges that make up White Rock rise about 300 meters (1,000 feet) above Pollock Crater's floor, which shows as dark lanes cutting into the light-colored formation.

Both TES and THEMIS can determine how solid the Martian surface materials are by how fast they heat up in daytime and cool off at night. The results show that while White Rock's light material may be dust-like in color and spectrum, it doesn't behave as loose dust does. Instead, some process turned it at least partly solid.

A similar-looking feature in Ganges Chasma may have formed the same way as White Rock.

Wandering Dunes

While the light material stands up as buttes and ridges, lots of loose material nonetheless surrounds White Rock. At the feature's northern end lies a field of dunes made of dark, basaltic sand grains.

The large image shows more dunes and accumulations of dark sand to the north and west of White Rock. The sand grains probably eroded from the lava that covers the floor of Pollack.

The dune shapes seen here suggest that some winds blew from the east (or southeast). It is possible these were funneled by the channel, some 500 meters (1,500 feet) wide, that cuts straight through White Rock. Other dunes not far away, however, suggest winds from the west.

Outliers

This unnamed impact crater lies less than 10 km southeast of White Rock. Some 2.4 km (1.5 mi) wide and about 40 meters (135 feet) deep, it's about as ordinary a small impact crater as could be.

Except for that tiny white bump on its floor. The bump, some 150 meters (500 feet) across, may be a remnant of the same material White Rock is made from.

As scientists reconstruct it, long ago the whole floor of Pollack may have been covered thickly with a light-toned, dusty material that blew in from elsewhere. Some dry process then compacted the material, turning it into something more durable than dust but softer than rock.

Later, winds began to erode White Rock's material, carrying off the debris as dust. Slowly, White Rock shrank until it reached its present size. Around its edges, however, a few outlying remnants still stand like icebergs in a sea.