The Cataracts of Kasei

One glance at Kasei Valles tells you that water — enormous, gushing floods of it — shaped the valley's development. Kasei and several other channels in the area around Chryse Planitia were the first Martian features to be identified, from Mariner 9 images in the early 1970s, as the products of catastrophic outpourings of water.

Kasei stretches more than 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) from Echus Chasma on the north side of Valles Marineris to its mouth at the edge of the Chryse basin, where it spreads 400 km (250 mi) wide. At any point along its course, you can pore over detailed spacecraft images from orbit and find a wealth of water-made features.

The section shown here centers on the lower part of the valley, which flows downstream from left to right. (A small portion of Kasei's course, far upstream from this area, has already been featured.) This image is a large mosaic that will reward considerable zooming-in, and if you wish for a larger "window" to explore within, get the downloadable .PNG file (see link at right), 30 MB in size.

In the center, atop a broad island-mesa, lies the large impact crater Sharonov, 100 km (62 mi) wide. Channels swerve around the mesa, which stands 2,000 meters (6,600 feet) higher than the channel beds flanking it. The channel to the north is called Lobo Vallis; that to the south is called, unsurprisingly, Kasei South.

To the southwest of the big mesa lie two parts of the Kasei South floor that contain gigantic dry cataracts — waterfalls — bigger than any found elsewhere on Mars or Earth.

The image above consists of infrared frames taken in late afternoon by the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) on NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter. Orbiting Mars every two hours, THEMIS scans the surface below in five visible and 10 infrared bands. The smallest details it can detect at infrared wavelengths are 100 meters (330 feet) wide; at visual wavelengths, THEMIS has imaged selected regions at 18-meter (59 feet) resolution.

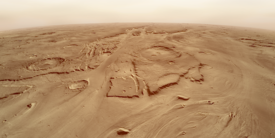

Cataract One

Cataract One

Just to the north lies a stretch of eroded, grooved channel floor with a rough appearance and a horseshoe-shaped edge. The scientists who first identified this feature as a waterfall searched for a terrestrial analog feature, finally settling on the 120-meter Dry Falls cataract in Grand Coulee, part of the Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington State.

On Mars, however, the cataract scale is several times larger. The Kasei dry falls have a vertical drop of 400 to 500 meters (1,300 to 1,600 ft) and the lip of the falls can be traced for more than 100 kilometers. As another, more familiar comparison, Niagara Falls stands about 50 meters high and the combined length of the American and Canadian Falls adds up to just 1.1 km (3,700 ft).

For all the jokes it sometimes occasions, Niagara Falls, as experienced at close range, is a powerful and impressive natural feature. And to think of seeing Kasei in full flood! The Martian cataracts would have been one of the most spectacular sights on any planet anywhere.

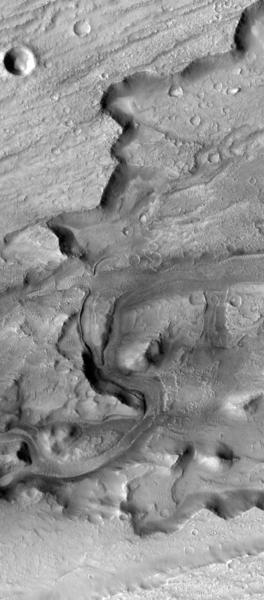

Cataract Two

Cataract TwoThe second dry waterfall, similar in size, lies to the southeast of the first example. It shows a roughly equal amount of sculpture by floods.

Scientists think that both cataracts now lie far upstream from where they first formed. (The same holds for Niagara, too, which has retreated about 11 km during the last 11,000 years.) The southern Kasei channel narrows directly south of Sharonov Crater, and the squeeze likely sped up the water flow through the narrows. That would have boosted greatly the floods' erosive power.

Here as in so many places on Mars, the bedrock consists of basalt (lava) sheets. When basalt cools, it shrinks and commonly develops small cracks and joints. At peak flow, floodwaters dug into the fabric of the channel floor, wielding immense hydraulic force to loosen and carry away everything that wasn't anchored tightly.

As floods poured over the cataracts, joints in the rock at the top of the cliff would be widened, and the plunging waters would steadily undermine the cliff face. The natural result is a headward (upstream) migration of the edge of the cataract. No one knows how far the megafloods drove the cataracts headward, but estimates run 150 to 250 km (95 to 150 mi).

The southern Kasei channel bed is now flat and all but featureless downstream from the cataracts. Even when imaged at a resolution of only a few feet (with the HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter), the channel bed shows only small drifts and dunes of dust, a few impact craters, and patterns of low, narrow ridges oriented in random loops and ovals. These may be evidence of either lavaflows or plates of ice and frozen mud, with the ridges being created as the plates bumped and rubbed together.

In any case, little remains in the channel bed to testify to the immense geological violence that played out here.

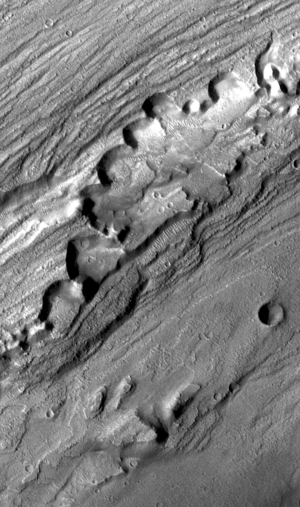

Streamlines

StreamlinesThis part of the valley lacks large cataracts, but shows an abundance of streamlined islands and ridges, all aligned with the flow. From the lack of abrupt features, scientists think the flow here was less than to the south, and perhaps also the bedrock shaped by the flow was softer and easier to erode.

Here we see an impact that left a crater in the channel. Its rim and outer flanks acted as an anchor and shield, behind which the channel surface was partly protected from erosion by floodwaters. It's also likely that some debris carried downstream could have drifted into the lee of the crater, where the water flowed more slowly. This would have given the entrained material an opportunity to drop out of the flow and contribute to the pennant-like ridge growing behind the crater.

.

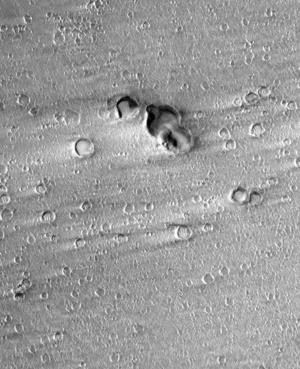

Streaking

StreakingThe tails are made of light-toned dust, the same as that falling out of the air all the time all over Mars. They created by easterly winds blowing up-canyon. As the wind flowed over the craters, their raised rims make the wind flow slower close to the ground, leaving sand particles in place. With the sand left undisturbed, the dust also remained in place. Elsewhere, however, the winds agitated the sand, lifting the dust particles so the wind could carry them away.

To THEMIS' infrared eyes, darkness indicates cool temperatures while brightness denotes warmth. The dust tails look dark in daytime infrared images because the dust's higher reflectivity prevents it from absorbing as much heat from sunlight. This keeps the dust a few degrees cooler, thus darker, than the surrounding rocky ground.

In nighttime infrared images, two effects cause the dust tails to look dark as well. First, being light in color the dust streaks never became as warm as the ground during daytime. Second, in a desert climate — which Mars has in spades — dust cools off quickly compared to rockier material. Thus by the time THEMIS flies over the streaks deep in the wee hours before sunrise, the dust has shed its heat and become cold and dark

.

Vital Statistics

Cataract One

One of two now-dry waterfalls in the Kasei South channel. The channel bed is deeply grooved by the floodwaters' scouring. While such features exist on Earth, the examples in Kasei are many times larger. This scene, about 8 km (5 mi) wide, is part of image P05_002814_2051_XI_25N061W, taken by the CTX camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Download Original

Cataract Two

The cliffs that form the dry waterfall here extend to the right (beyond the image) for another 100 kilometers. This scene, 11 km (7 mi) wide, is part of THEMIS VIS image V10088003.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University

Download Original

Streamlines

An impact crater made a natural obstacle in the bed of Lobo Vallis. The flood in this part of the valley was not deep enough to engulf the crater. Instead the water flowed around it, carving a streamlined mesa behind. The scene, 12.6 km (7.8 mi) wide, is part of THEMIS VIS image V05869018.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University

Download Original

Streaking

Bright dust lies behind craters, where winds from the east (right) have left it undisturbed. The craters forming a group are likely "secondaries" — craters left by debris ejected from another, yet-unidentified impact in the vicinity. This scene, 8.2 km (5.1 mi) wide, is part of image P17_007640_2061_XN_26N061W, taken by the CTX camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Download Original