Hypanis Valles

Having followed the water — and, in many places, found it in the form of ice — NASA's Mars focus is shifting toward environments that likely show hospitality for life, either present life or (what's far more likely) ancient, long gone life.

What NASA is looking for, in a word, is habitability.

This region — Hypanis Valles — was once considered a potential landing site for NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), the next-generation rover due for launch in late 2011. MSL's mission is to find and study habitable environments, old or new.

Other locations beckoned more enticingly, however, and Hypanis didn't make the MSL short list. Yet it remains an intriguing place because of the thin fluvial channel that threads through the scene, plus the associated broad, bright patch in the center.

Hypanis lies in Xanthe Terra, a low cratered region on the northeast side of Valles Marineris. The terrain slopes gently down into the Chryse basin, part of the vast northern lowlands.

Several prominent channels slice through Xanthe, chiefly Maja and Shalbatana Valles. These are relics of the era of outflows, when a warmer and wetter Mars than today saw floodwaters as great as any on Earth or greater.

The image is a mosaic of daytime infrared frames taken by the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS), a 10-band infrared and visual camera on NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter. Sweeping around Mars with Odyssey's 2-hour orbit since 2002, THEMIS has woven a tight network of images that now completely cover the planet at 100-meter (330-foot) resolution. THEMIS has also imaged selected regions at 18-meter (59 feet) resolution using its visual-wavelength imager.

Meandering Along

Meandering Along Dry Bed

Dry BedA closer look with the THEMIS camera's visual imager (with an 18 m or 59 ft resolution) shows that the patch isn't as smooth as first glance suggests. Instead, a sheet of light material has spread across the course of Hypanis, perhaps created as water flowing downstream to the north slackened its pace and spread across the flats.

The closeup view at right shows two craters that look buried to the rim-tops by this layer. At some later point, renewed flow down Hypanis poured over the light-toned layer and cut a fresh channel through it, about 10 to 15 meters deep.

Layer-Cake Mesa

Layer-Cake Mesa Frost Heave?

Frost Heave?

Vital Statistics

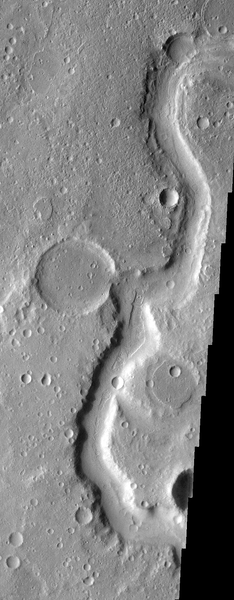

Meandering Along

Hypanis Valles cut a winding channel as it flowed across generally flat terrain toward the northern lowlands. This image, about 15 km wide, is part of THEMIS VIS frame V27172034.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University)

Download Original

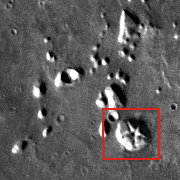

Dry Bed

Part of the Hypanis channel has carved into a light-toned layer of seidments, apparently washing them a gentle slope to the north (upward in the image). This view, 12 km wide, is part of THEMIS VIS image V11585009.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University)

Download Original

Layer-Cake Mesa

A close look at the mesa reveals that it is made from many sheets of thin sediments piled smoothly on top of each other. These may be windblown dust or volcanic ash — or possibly sediments deposited by water. This image, 5 km wide, is part of image PSP_010817_1920 taken by the HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona)

Download Original

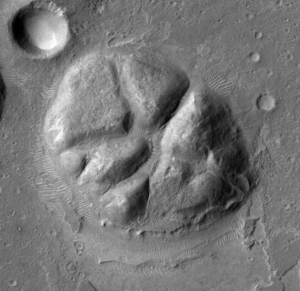

Frost Heave?

The origin of this feature is not known for certain, but it resembles Arctic features on Earth called pingos. A pingo develops when ice lifts part of the ground, making a giant frost heave. This image, about 4 km wide, is part of image P15_007033_1915_XI_11N045W taken by the Context Imager (CTX) on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

Download Original